There has been plenty already written about the merits or otherwise of introducing the Mark. Whether it’s needed or not is not the point of this article. It’s here to stay so what can teams expect and how might they use the new rule to gain an advantage.

For the team kicking the ball out I think the mark will offer little or no advantage. Maybe in the last few minutes of a game if you want to slow things down, but you only have 5 seconds to kick the ball so you better be quick.

Having sat in on a recent rules presentation at the National Coaching Conference in early January I believe the biggest issue with the Mark could be the infringements that happen around it rather than the Mark itself.

The Mark is borrowed from the AFL but in AFL the onus is on the player who caught the ball (took the mark) to move back. The point at where the mark is taken is where the defender can stand. They are under no onus to move back. They stand there ground and if the marking player passes that point(allowing for momentum) he is deemed to be playing on and can be tackled.

Here is what the AFL rule states;

16.1.1 Standing the Mark

When a Player is awarded a Mark or Free Kick or is Kicking into play after a Behind has been scored, one Player from the opposing Team may stand at the position on the Playing Surface where the Mark or Free Kick was awarded or where the field Umpire otherwise directs the Player to stand. The position on the Playing Surface where the opposing Player stands is known as “the mark”.

16.1.2 Protected Area

The Protected Area is a corridor which extends from 5 metres either side of the mark to 5 metres either side of, and a 5-metre radius behind, the Player with the football, as illustrated in Diagram 2. No Player shall enter and remain in the Protected Area unless the field Umpire calls “Play On” or the Player is accompanying or following within 5 metres of their opponent.

In the new rule introduced for football the onus is on the defending player (player who didn’t win the mark) to retreat 13m or if the player who made the mark decides to play on to let him take 4 steps (or see (I) below).

If not, a free kick is awarded, which can be taken by any player.

Because of the proximity to the opposition goal the Mark is much more likely to offer an advantage to the non-kicking team than it is to the kicking team and this secondary foul issue might be the reason.

Let’s look at a couple of scenarios;

Scenario 1; You take your kickout, it travels past the 45 and a successful mark is taken by the team who kicked the ball out. The player decides not to play on but take the ‘free kick’ option. The rule states he has 5 seconds to kick the ball and as with free kick rules the ball must travel 13m. Failure to take the kick on time will result in a throw up. While failure to kick it the required distance will result in a free to the opposition.

It might be the case that not kicking 13 happens very infrequently currently, but players aren’t taking frees with a 5 second time pressure.

The decision making of the player who took the mark will need to be sharp and those around him will need to keep their distance. While attacking teams might lose the initial kickout there could be an upside to having pressure on high up the pitch and forcing the foul or forcing the team to aimlessly kick it away.

Scenario 2; The attaching team win the Mark.

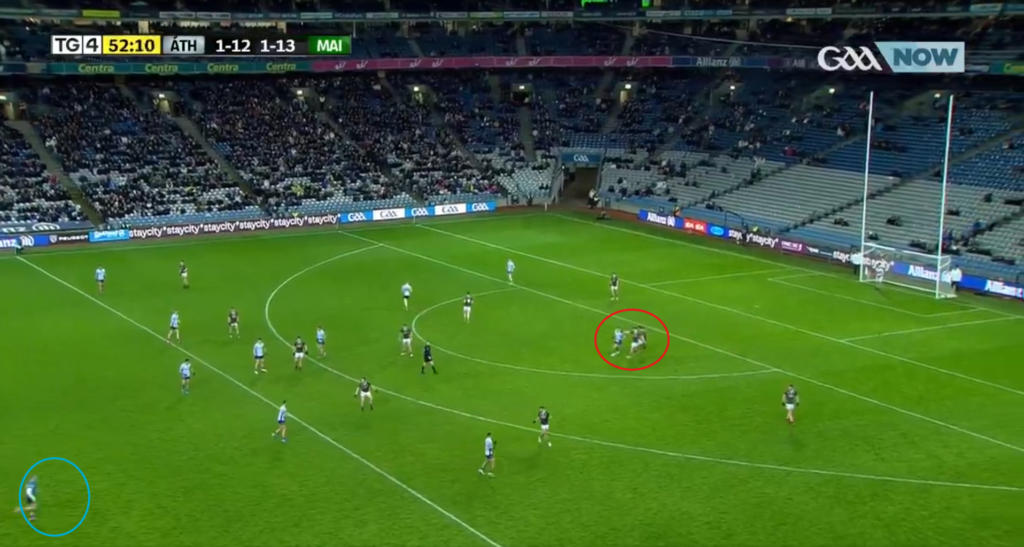

This is the one that I could see causing the most issues and perhaps will result in teams at least exploring the possibility of pushing up on opposition kickouts, even if that’s just for key moments of the game.

The same 5 second rule applies to the player taking the mark, So while you have the opportunity to shoot, it’s only the player who catches the ball that can shoot directly from the mark. Considering the time pressure, the likely distance from goal (min 45m) and the chance of your free taker taking the mark I see direct shots as a rare occurrence.

Again though I see the secondary fouls, infringements around the Mark, as being the most dangerous and causing the most controversy. These are as likely to happen in wither direction but having the ball moved from your 45 to your 65 doesn’t carry the same importance as having it moved from outside the scoring zone to inside it.

In the FAQ section on the GAA site there is the following;

8. If the player who has been awarded the Mark chooses to take a free kick and a player from the opposing team blocks or attempts to block that kick within 13m or interferes with the player who has chosen to take the kick, what is the award?

A free kick 13m more advantageous shall be awarded.

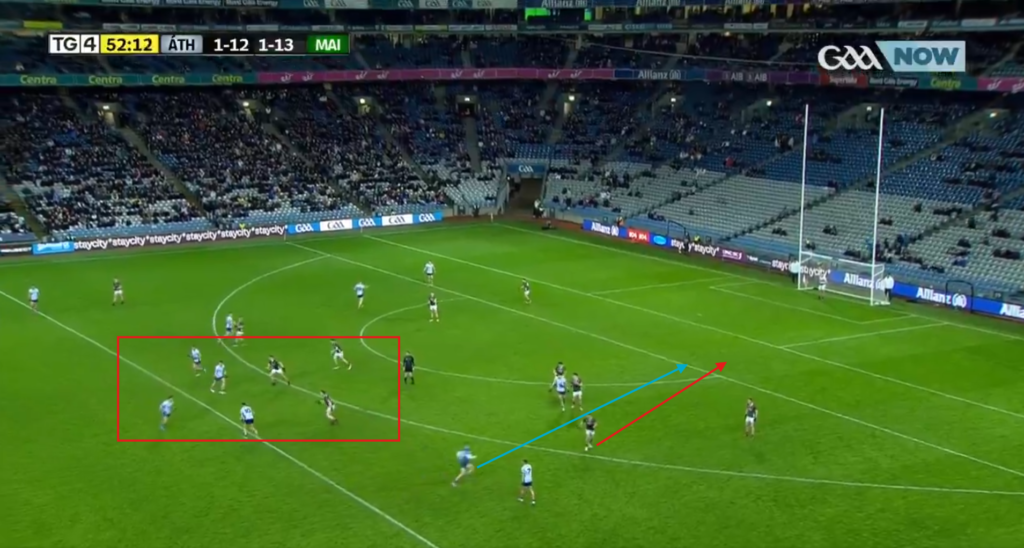

Case 1; Diarmuid Connolly catches the ball and Lee Keegan doesn’t retreat 13m quick enough the ball gets moved forward 13m and can now be given to Dean Rock to take the subsequent free. While the advantage is minimal from taking the mark, it’s much greater if you can ‘win’ a secondary free.

Discipline will be important but also referees will have to deal with quick free attempts where the defending player hasn’t retreated or maybe hasn’t had time to.

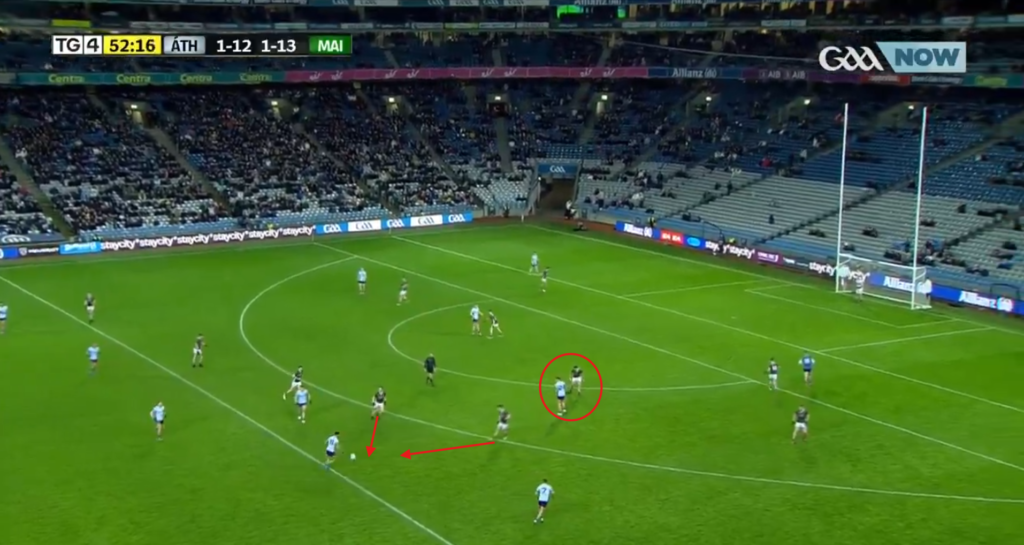

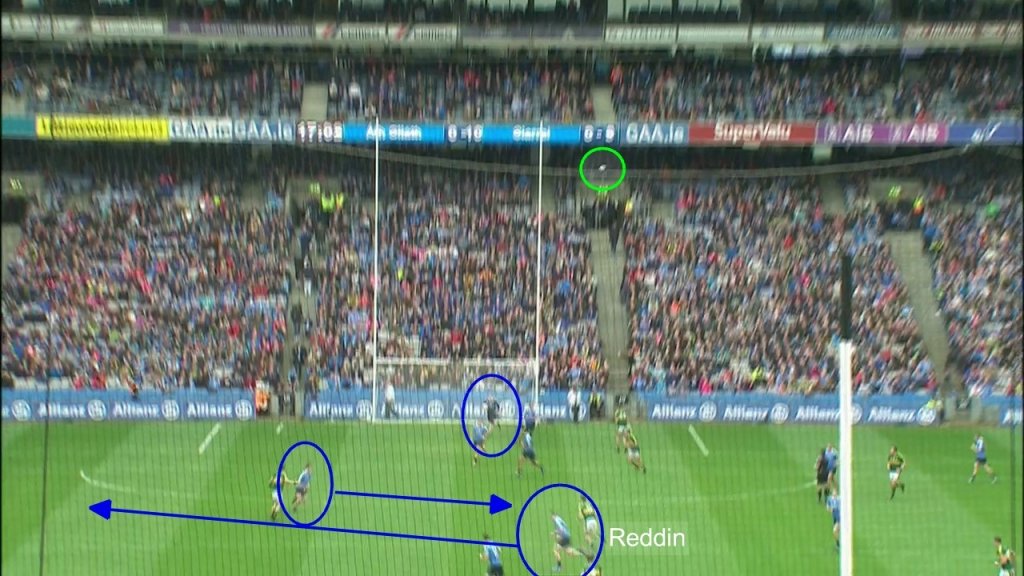

Case 2; Connolly decides to play on immediately following the Mark;

The rule states;

(b) Play on immediately

(i) In this circumstance the player may not be challenged for the ball until he carries the ball up to a maximum of four consecutive steps or holds the ball for no longer than the time needed to take four steps and/or makes one act of kicking, handpassing, bouncing or toe-tapping the ball.

(ii) If the Player is illegally challenged, a free kick shall be awarded to his team from the point at which the challenge is made, and this free kick may be taken by any player on his team.

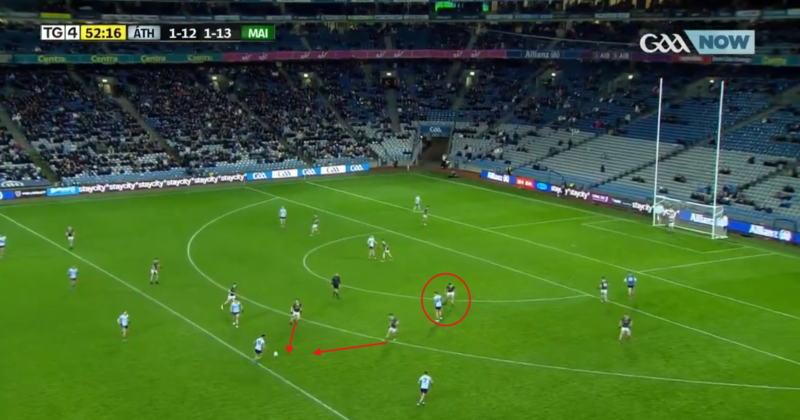

This is where the difference the Mark rule as used in AFL and the new GAA is especially important.

Suppose in our fictional example Connolly catches a mark and decides to play on.

Lee Keegan can’t tackle him for 4 steps. In AFL Keegan would be under no obligation to retreat or move out of the way. As long as he holds his position at the point of the mark it’s fair. In Football that’s not the case, he can be in close proximity but he can’t tackle Connolly.

How disciplined players are around this will be key. Letting any forward take 4 steps towards goal will not come easy to tenacious defenders. Referees interpreting when a ‘tackle’ is made will also be key. Staying close enough but not actually tackling him will require some fine tuning.

The chance of winning an opposition long kickout (past the 45m line) is currently 45%. If the non-kicking team feel that the mark offers them an improved advantage, from either an initial mark or forcing secondary frees, maybe we will see teams push up more, less short kickouts and more high fielding. Maybe?

The common consensus is that nothing will really change, but no one knows for sure. There are plenty of bright minds in the game who will be doing more than just saying ‘this won’t change a thing’. They’ll be experimenting, planning and watching endless hours of tape.

It won’t surprise me at all if somebody has something up their sleeve to exploit this new rule, but it’s also very likely we will have to wait until August before we see it.